Published paper: Knowledge gaps for environmental antibiotic resistance

The outcomes from a workshop arranged by JPIAMR, the Swedish Research Council (VR) and CARe were just published as a short review paper in Environment International. In the paper, which was mostly moved forward by Prof. Joakim Larsson at CARe, we describe four major areas of knowledge gaps in the realm of environmental antibiotic resistance (1). We then highlight several important sub-questions within these areas. The broad areas we define are:

- What are the relative contributions of different sources of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria into the environment?

- What is the role of the environment as affected by anthropogenic inputs (e.g. pollution and other activities) on the evolution (mobilization, selection, transfer, persistence etc.) of antibiotic resistance?

- How significant is the exposure of humans to antibiotic resistant bacteria via different environmental routes, and what is the impact on human health?

- What technological, social, economic and behavioral interventions are effective to mitigate the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance via the environment?

Although much has been written on the topic before (e.g. 2-12), I think it is unique that we collect and explicitly point out areas in which we are lacking important knowledge to build accurate risk models and devise appropriate intervention strategies. The workshop was held in Gothenburg on the 27–28th of September 2017. The workshop leaders Joakim Larsson, Ana-Maria de Roda Husman and Ramanan Laxminarayan were each responsible for moderating a breakout group, and every breakout group was tasked to deal with knowledge gaps related to either evolution, transmission or interventions. The reports of the breakout groups were then discussed among all participants to clarify and structure the areas where more research is needed, which boiled down to the four overarching critical knowledge gaps described in the paper (1).

This is a short paper, and I think everyone with an interest in environmental antibiotic resistance should read it and reflect over its content (because, we may of course have overlooked some important aspect). You can find the paper here.

References

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, 117, 132–138 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.041

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Martinez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F: What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2015, 13:116–123. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3399

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 369 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1

- Ashbolt NJ, Amézquita A, Backhaus T, Borriello P, Brandt KK, Collignon P, et al.: Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) for Environmental Development and Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 993–1001 (2013)

- Pruden A, Larsson DGJ, Amézquita A, Collignon P, Brandt KK, Graham DW, et al.: Management options for reducing the release of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes to the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 878–85 (2013).

- Gillings MR: Evolutionary consequences of antibiotic use for the resistome, mobilome and microbial pangenome. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 4 (2013).

- Baquero F, Alvarez-Ortega C, Martinez JL: Ecology and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 1, 469–476 (2009).

- Baquero F, Tedim AP, Coque TM: Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 15 (2013).

- Berendonk TU, Manaia CM, Merlin C et al.: Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 310–317 (2015).

- Hiltunen T, Virta M, Laine A-L: Antibiotic resistance in the wild: an eco-evolutionary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372 (2017) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0039.

- Martinez JL: Bottlenecks in the transferability of antibiotic resistance from natural ecosystems to human bacterial pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2, 265 (2011).

Published paper: A novel Na-binding site in sialic acid symporters

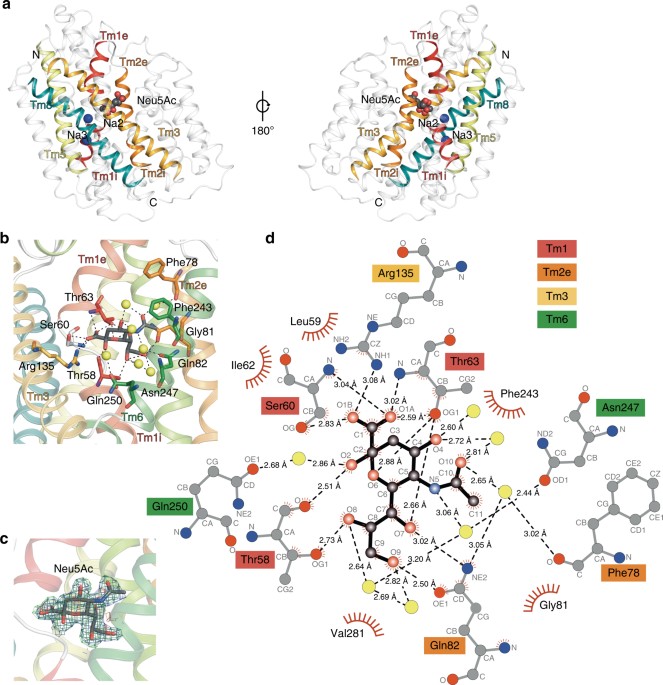

I have been quite occupied with other things the last couple of days, so I am late on the ball here. Anyway, on May 1st, Nature Communications published a paper on the protein structure of SiaT, a sialic acid transporter from Proteus mirabilis (1). Many pathogens use sialic acids as an energy source or as an external coating to evade the immune defense (2). Therefore, many bacteria that colonize sialylated environments have transporters which specifically import sialic acids. SiaT is one of those transporters, belonging to the sodium solute symporter (SSS) family (3) (with for some weird reason is associated with the Pfam family “SSF”, an eternal source of confusion in discussions within this project). The SSS proteins use Na+ gradients to drive the import of desired substrates (4). Based on the protein structure, our team found that SiaT binds two Na+ ions. One binds to the conserved, well-known, Na2 site, but the other Na+ binds to a new position, which we term Na3. This position (this is where my part of the work comes in) is conserved in many SSS family members. We finally used functional and molecular dynamics studies to validate the substrate-binding site and demonstrate that both Na+ sites regulate N-acetylneuraminic acid transport.

As I hinted, i am not venturing into protein structures – that part of this work has been performed by an excellent team associated with Dr. Rosmarie Friemann. Instead, my part is essentially summarized in these two sentences of the manuscript: “We analysed all SSS sequences that contained the primary Na2 site (21,467) to determine the degree of conservation of the Na3 site, allowing for threonine at either Ser345 or Ser346. Na3 is present in 19.6% (4212) of these sequences including hSGLT1, which transports two Na+, but not vSGLT or hSGLT2, which transport only one Na+” (1). That’s a few months of works condensed into 55 words. Still, the exciting thing here is that we find an evolutionary conserved Na-binding site, which has so far eluded detection.

The results of this work provides a better understanding of how secondary active transporters harness additional energy from ion gradients. It may be possible to exploit differences in this mechanism between different SSS family members (and other transporters with the LeuT fold) to develop new antimicrobials, something that is urgently needed in the face of the rapidly increasing antibiotic resistance.

References

- Wahlgren WY°, North RA°, Dunevall E°, Paz A, Scalise M, Bisognano P, Bengtsson-Palme J, Goyal P, Claesson E, Caing-Carlsson R, Andersson R, Beis K, Nilsson U, Farewell A, Pochini L, Indiveri C, Grabe M, Dobson RCJ, Abramson J, Ramaswamy S, Friemann R: Substrate-bound outward-open structure of a Na+-coupled sialic acid symporter reveals a novel Na+ site. Nature Communications, 9, 1753 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04045-7

- Vimr ER, Kalivoda KA, Deszo EL, Steenburgen SM: Diversity of microbial sialic acid metabolism. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 68, 132–153 (2004).

- North RA, Horne CR, Davies JS, Remus DM, Muscroft-Taylor AC, Goyal P, Wahlgren WY, Ramaswamy S, Friemann R, Dobson RCJ: “Just a spoonful of sugar…”: import of sialic acid across bacterial cell membranes. Biophysical Reviews, 10, 219–227 (2017).

- Severi E, Hosie AH, Hawkhead JA, Thomas GH: Characterization of a novel sialic acid transporter of the sodium solute symporter (SSS) family and in vivo comparison with known bacterial sialic acid transporters. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 304, 47–54 (2010).

Published paper: Selective concentrations for ciprofloxacin

My colleagues in Gothenburg have published a new paper in Environment International, in which I was involved in the bioinformatics analyses. In the paper, for which Nadine Kraupner did the lion’s share of the work, we establish minimal selective concentrations (MSCs) for resistance to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin in Escherichia coli grown in complex microbial communities (1). We also determine the community responses at the taxonomic and resistance gene levels. Nadine has made use of Sara Lundström’s aquarium system (2) to grow biofilms in the exposure of sublethal levels of antibiotics. Using the system, we find that 1 μg/L ciprofloxacin selects for the resistance gene qnrD, while 10 μg/L ciprofloxacin is required to detect changes of phenotypic resistance. In short, the different endpoints studied (and their corresponding MSCs) were:

- CFU counts from test tubes, grown on R2A plates with 2 mg/L ciprofloxain – MSC = 5 μg/L

- CFU counts from aquaria, grown on R2A plates with 0.25 or 2 mg/L ciprofloxain – MSC = 10 μg/L

- Chromosomal resistance mutations – MSC ~ 10 μg/L

- Increased resistance gene abundances, metagenomics – MSC range: 1 μg/L

- Changes to taxonomic diversity – 1 µg/L

- Changes to taxonomic community composition – MSC ~ 1-10 μg/L

We have previously reported a predicted no-effect concentration for resistance of 0.064 µg/L for ciprofloxacin (3), which corresponds fairly well with the MSCs determined experimentally here, being around a factor of ten off. However, we cannot exclude that in other experimental systems, the selective effects of ciprofloxacin could be even lower and thus the predicted PNEC may still be relevant. The selective concentrations we report for ciprofloxacin are close to those that have been reported in sewage treatment plants (3-5), suggesting the possibility for weak selection of resistance. Several recent reports have underscored the need to populate the this far conceptual models for resistance development in the environment with actual numbers (6-10). Determining selective concentrations for different antibiotics in actual community settings is an important step on the road towards building accurate quantitative models for resistance emergence and propagation.

References

- Kraupner N, Ebmeyer S, Bengtsson-Palme J, Fick J, Kristiansson E, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ: Selective concentration for ciprofloxacin in Escherichia coli grown in complex aquatic bacterial biofilms. Environment International, 116, 255–268 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.029 [Paper link]

- Lundström SV, Östman M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Rutgersson C, Thoudal M, Sircar T, Blanck H, Eriksson KM, Tysklind M, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ: Minimal selective concentrations of tetracycline in complex aquatic bacterial biofilms. Science of the Total Environment, 553, 587–595 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.103 [Paper link]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environment International, 86, 140-149 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015

- Michael I, Rizzo L, McArdell CS, Manaia CM, Merlin C, Schwartz T, Dagot C, Fatta-Kassinos D: Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: a review. Water Research, 47, 957–995 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.027

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Hammarén R, Pal C, Östman M, Björlenius B, Flach C-F, Kristiansson E, Fick J, Tysklind M, Larsson DGJ: Elucidating selection processes for antibiotic resistance in sewage treatment plants using metagenomics. Science of the Total Environment, 572, 697–712 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.228

- Ågerstrand M, Berg C, Björlenius B, Breitholtz M, Brunstrom B, Fick J, Gunnarsson L, Larsson DGJ, Sumpter JP, Tysklind M, Rudén C: Improving environmental risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals. Environmental Science and Technology (2015). doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b00302

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance: JPIAMR Workshop on Environmental Dimensions of AMR: Summary and recommendations. JPIAMR (2017). [Link]

- Angers A, Petrillo P, Patak, A, Querci M, Van den Eede G: The Role and Implementation of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies in the Coordinated Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance. JRC Conference and Workshop Report, EUR 28619 (2017). doi: 10.2760/745099

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, in press (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.041

New preprint: benchmarking resistance gene identification

This weekend, F1000Research put online the non-peer-reviewed version of the paper resulting from a workshop arranged by the JRC in Italy last year (1). (I will refer to this as a preprint, but at F1000Research the line is quite blurry between preprint and published paper.) The paper describes various challenges arising from the process of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines (2) in the identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next generation sequencing data.

The paper discusses issues about the benchmarking datasets used, testing samples, evaluation criteria for the performance of different tools, and how the benchmarking dataset should be created and distributed. Specially, we address the following questions:

- How should a benchmark strategy handle the current and expanding universe of NGS platforms?

- What should be the quality profile (in terms of read length, error rate, etc.) of in silico reference materials?

- Should different sets of reference materials be produced for each platform? In that case, how to ensure no bias is introduced in the process?

- Should in silico reference material be composed of the output of real experiments, or simulated read sets? If a combination is used, what is the optimal ratio?

- How is it possible to ensure that the simulated output has been simulated “correctly”?

- For real experiment datasets, how to avoid the presence of sensitive information?

- Regarding the quality metrics in the benchmark datasets (e.g. error rate, read quality), should these values be fixed for all datasets, or fall within specific ranges? How wide can/should these ranges be?

- How should the benchmark manage the different mechanisms by which bacteria acquire resistance?

- What is the set of resistance genes/mechanisms that need to be included in the benchmark? How should this set be agreed upon?

- Should datasets representing different sample types (e.g. isolated clones, environmental samples) be included in the same benchmark?

- Is a correct representation of different bacterial species (host genomes) important?

- How can the “true” value of the samples, against which the pipelines will be evaluated, be guaranteed?

- What is needed to demonstrate that the original sample has been correctly characterised, in case real experiments are used?

- How should the target performance thresholds (e.g. specificity, sensitivity, accuracy) for the benchmark suite be set?

- What is the impact of these performance thresholds on the required size of the sample set?

- How can the benchmark stay relevant when new resistance mechanisms are regularly characterized?

- How is the continued quality of the benchmark dataset ensured?

- Who should generate the benchmark resource?

- How can the benchmark resource be efficiently shared?

Of course, we have not answered all these questions, but I think we have come down to a decent description of the problems, which we see as an important foundation for solving these issues and implementing the benchmarking standard. Some of these issues were tackled in our review paper from last year on using metagenomics to study resistance genes in microbial communities (3). The paper also somewhat connects to the database curation paper we published in 2016 (4), although this time the strategies deal with the testing datasets rather than the actual databases. The paper is the first outcome of the workshop arranged by the JRC on “Next-generation sequencing technologies and antimicrobial resistance” held October 4-5 last year in Ispra, Italy. You can find the paper here (it’s open access).

References and notes

- Angers-Loustau A, Petrillo M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Berendonk T, Blais B, Chan KG, Coque TM, Hammer P, Heß S, Kagkli DM, Krumbiegel C, Lanza VF, Madec J-Y, Naas T, O’Grady J, Paracchini V, Rossen JWA, Ruppé E, Vamathevan J, Venturi V, Van den Eede G: The challenges of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines in the identification of antimicrobial resistance determinants using next generation sequencing technologies. F1000Research, 7, 459 (2018). doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14509.1

- You may remember that I hate the term “pipeline” for bioinformatics protocols. I would have preferred if it was called workflows or similar, but the term “pipeline” has taken hold and I guess this is a battle where I have essentially lost. The bioinformatics workflows will be known as pipelines, for better and worse.

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ, Kristiansson E: Using metagenomics to investigate human and environmental resistomes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 72, 2690–2703 (2017). doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx199

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Boulund F, Edström R, Feizi A, Johnning A, Jonsson VA, Karlsson FH, Pal C, Pereira MB, Rehammar A, Sánchez J, Sanli K, Thorell K: Strategies to improve usability and preserve accuracy in biological sequence databases. Proteomics, 16, 18, 2454–2460 (2016). doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600034

Published paper: Annotating fungi from the built environment part II

MycoKeys earlier this week published a paper describing the results of a workshop in Aberdeen in April last year, where we refined annotations for fungal ITS sequences from the built environment (1). This was a follow-up on a workshop in May 2016 (2) and the results have been implemented in the UNITE database and shared with other online resources. The paper has also been highlighted at microBEnet. I have very little time to further comment on this at this very moment, but I believe, as I wrote last time, that distributed initiatives like this (and the ones I have been involved in in the past (3,4)) serve a very important purpose for establishing better annotation of sequence data (5). The full paper can be found here.

References

- Nilsson RH, Taylor AFS, Adams RI, Baschien C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Cangren P, Coleine C, Daniel H-M, Glassman SI, Hirooka Y, Irinyi L, Iršenaite R, Martin-Sánchez PM, Meyer W, Oh S-O, Sampaio JP, Seifert KA, Sklenár F, Stubbe D, Suh S-O, Summerbell R, Svantesson S, Unterseher M, Visagie CM, Weiss M, Woudenberg J, Wurzbacher C, Van den Wyngaert S, Yilmaz N, Yurkov A, Kõljalg U, Abarenkov K: Annotating public fungal ITS sequences from the built environment according to the MIxS-Built Environment standard – a report from an April 10-11, 2017 workshop (Aberdeen, UK). MycoKeys, 28, 65–82 (2018). doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.28.20887 [Paper link]

- Abarenkov K, Adams RI, Laszlo I, Agan A, Ambrioso E, Antonelli A, Bahram M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Bok G, Cangren P, Coimbra V, Coleine C, Gustafsson C, He J, Hofmann T, Kristiansson E, Larsson E, Larsson T, Liu Y, Martinsson S, Meyer W, Panova M, Pombubpa N, Ritter C, Ryberg M, Svantesson S, Scharn R, Svensson O, Töpel M, Untersehrer M, Visagie C, Wurzbacher C, Taylor AFS, Kõljalg U, Schriml L, Nilsson RH: Annotating public fungal ITS sequences from the built environment according to the MIxS-Built Environment standard – a report from a May 23-24, 2016 workshop (Gothenburg, Sweden). MycoKeys, 16, 1–15 (2016). doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.16.10000

- Kõljalg U, Nilsson RH, Abarenkov K, Tedersoo L, Taylor AFS, Bahram M, Bates ST, Bruns TT, Bengtsson-Palme J, Callaghan TM, Douglas B, Drenkhan T, Eberhardt U, Dueñas M, Grebenc T, Griffith GW, Hartmann M, Kirk PM, Kohout P, Larsson E, Lindahl BD, Lücking R, Martín MP, Matheny PB, Nguyen NH, Niskanen T, Oja J, Peay KG, Peintner U, Peterson M, Põldmaa K, Saag L, Saar I, Schüßler A, Senés C, Smith ME, Suija A, Taylor DE, Telleria MT, Weiß M, Larsson KH: Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of Fungi. Molecular Ecology, 22, 21, 5271–5277 (2013). doi: 10.1111/mec.12481

- Nilsson RH, Hyde KD, Pawlowska J, Ryberg M, Tedersoo L, Aas AB, Alias SA, Alves A, Anderson CL, Antonelli A, Arnold AE, Bahnmann B, Bahram M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Berlin A, Branco S, Chomnunti P, Dissanayake A, Drenkhan R, Friberg H, Frøslev TG, Halwachs B, Hartmann M, Henricot B, Jayawardena R, Jumpponen A, Kauserud H, Koskela S, Kulik T, Liimatainen K, Lindahl B, Lindner D, Liu J-K, Maharachchikumbura S, Manamgoda D, Martinsson S, Neves MA, Niskanen T, Nylinder S, Pereira OL, Pinho DB, Porter TM, Queloz V, Riit T, Sanchez-García M, de Sousa F, Stefaczyk E, Tadych M, Takamatsu S, Tian Q, Udayanga D, Unterseher M, Wang Z, Wikee S, Yan J, Larsson E, Larsson K-H, Kõljalg U, Abarenkov K: Improving ITS sequence data for identification of plant pathogenic fungi. Fungal Diversity, 67, 1, 11–19 (2014). doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0291-8

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Boulund F, Edström R, Feizi A, Johnning A, Jonsson VA, Karlsson FH, Pal C, Pereira MB, Rehammar A, Sánchez J, Sanli K, Thorell K: Strategies to improve usability and preserve accuracy in biological sequence databases. Proteomics, Early view (2016). doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600034

Published paper: Blastocystis and the intestinal microbiota

Yesterday, BMC Microbiology published a paper which I have co-authored with Joakim Forsell and his colleagues in at Umeå University. The paper (1) investigates the prevalence and subtype composition of Blastocystis – a eukaryotic microbe commonly present in the human intestine – among the 35 Swedish university students that we investigated for antibiotic resistance before and after travel to the Indian peninsula or Central Africa using shotgun metagenomics, and published in 2015 (2). In this paper, we used the same metagenomic data, but to assess the impact of travel on Blastocystis carriage and to understand the associations between Blastocystis and the bacterial gut microbiota. We found that 46% of the students carried Blastocystis before travel and 43% after. The two most commonly identified Blastocystis subtypes were ST3 and ST4, accounting for 20 of the 31 samples positive for Blastocystis. Interestingly, we detected no mixed subtype carriage in any individual, and all the ten individuals with a typable subtype before and after travel maintained their initial subtype.

Furthermore, we found that the composition of the gut bacterial community was not significantly altered between Blastocystis-carriers and non-carriers. Curiously, Blastocystis was accompanied with higher abundances of the bacterial genera Sporolactobacillus and Candidatus Carsonella. As perviously observed (3), Blastocystis carriage was positively associated with higher bacterial genus richness, and negatively correlated to the Bacteroides-driven enterotype. We, however, took this observation further, and could show that these associations were both largely driven by ST4 – a subtype commonly described in Europe – while the globally prevalent ST3 did not show such significant relationships.

The persistence of Blastocystis subtypes before and after travel indicates that long-term carriage of Blastocystis is common. The associations between Blastocystis and the bacterial microbiota found in this study could imply a link between Blastocystis and a healthy microbiota, as well as with diets high in vegetables. However, we cannot answer whether the associations between Blastocystis and the microbiota are resulting from the presence of Blastocystis per se, or are a prerequisite for colonization with Blastocystis, which are interesting opportunities for follow-up studies.

I think this type of data reuse for completely different questions is highly useful, and I am very happy that Joakim Forsell and his colleagues contacted me to hear if it was possible to do a Blastocystis screen of this data. The full paper can be read here.

References

- Forsell J, Bengtsson-Palme J, Angelin M, Johansson A, Evengård B, Granlund M: The relation between Blastocystis and the intestinal microbiota in Swedish travellers. BMC Microbiology, 17, 231 (2017). doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1139-7 [Paper link]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Angelin M, Huss M, Kjellqvist S, Kristiansson E, Palmgren H, Larsson DGJ, Johansson A: The human gut microbiome as a transporter of antibiotic resistance genes between continents. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 59, 10, 6551–6560 (2015). doi: 10.1128/AAC.00933-15 [Paper link]

- Andersen LO, Bonde I, Nielsen HB, Stensvold CR: A retrospective metagenomics approach to studying Blastocystis. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 91, fiv072 (2015). doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv072 [Paper link]

Published opinion piece: Protection goals and risk assessment

Recently, Le Page et al. published a paper in Environmental International (1), partially building on the predicted no-effect concentrations for resistance selection for 111 antibiotics that me and Joakim Larsson published around two years ago (2). In their paper, the authors stress that discharge limits for antibiotics need to consider their potency to affect both environmental and human health, which we believe is a very reasonable standpoint, and to which we agree. However, we do not agree on the authors’ claim that cyanobacteria would often be more sensitive to antibiotics than the most sensitive human-associated bacteria (1). Importantly, we also think that it is a bit unclear from the paper which protection goals are considered. Are the authors mainly concerned with protecting microbial diversity in ecosystems, protecting ecosystem functions and services, or protecting from risks for resistance selection? This is important because it influence why one would want to mitigate, and therefore who would perform which actions. To elaborate a little on our standpoints, we wrote a short correspondence piece to Environment International, which is now published (3). (It has been online for a few days, but without a few last-minute changes we did to the proof, and hence I’m only posting about it now when the final version is online.) There is indeed an urgent need for discharge limits for antibiotics, particularly for industrial sources (4) and such limits would have tremendous value in regulation efforts, and in development of environmental criteria within public procurement and generic exchange programs (5). Importantly, while we are all for taking ecotoxicological data into account when doing risk assessment, we think that there should be solid scientific ground for mitigations and that regulations need to consider the benefits versus the costs, which is what we want to convey in our response to Le Page et al.

References

- Le Page G, Gunnarsson L, Snape J, Tyler CR: Integrating human and environmental health in antibiotic risk assessment: a critical analysis of protection goals, species sensitivity and antimicrobial resistance. Environment International, in press (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.013

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environment International, 86, 140–149 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Protection goals must guide risk assessment for antibiotics. Environment International, in press (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.019

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Time to limit antibiotic pollution. The Medicine Maker, 0416, 302, 17–18 (2016). [Paper link]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Gunnarsson L, Larsson DGJ: Can branding and price of pharmaceuticals guide informed choices towards improved pollution control during manufacturing? Journal of Cleaner Production, 171, 137–146 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.247

Published paper: Drug price is linked to environmental standards

Yesterday, Swedish television channel TV4 highlighted a recent publication by myself, Lina Gunnarsson and Joakim Larsson, in which we show that the price of pharmaceuticals is linked to the environmental standards of production countries. Surprisingly, however, this link seems to be mostly driven by whether the product is generic or original (branded), which in turns affect the prices.

In the study (1), published in Journal of Cleaner Production, we have used an exclusive set of Swedish sales data for pharmaceuticals combined with data on the origin of the active ingredients, obtained under an agreement to not identify individual manufacturers or products. We used this data to determine if price pressure and generic substitution could be linked to the general environmental performance and the corruption levels of the production countries, as measured by the Environmental Performance Index (2) and the Corruption Perception Index (3). In line with what we believed, India was the largest producer of generics, while Europe and the USA dominated the market for branded products (1). Importantly, we found that the price and environmental performance index of the production countries were linked, but that this relationship was largely explained by whether the product was original or generic.

To some extent, this relationship would allow buyers to select products that likely originate from countries that, in general terms, have better pollution control, which was also highlighted in the news clip that TV4 produced. However, what was lacking from that clip was the fact that this approach lacks resolution, because it does not say anything about the environmental footprint of individual products. We therefore conclude that to better allow consumers, hospitals and pharmacies to influence the environmental impact of their product choices, there is need for regulation and, importantly, transparency in the production chain, as has also been pointed out earlier (4,5). To this end, emissions from manufacturing need to be measured, allowing for control and follow-up on industry commitments towards sustainable manufacturing of pharmaceuticals (6). Since the discharges from pharmaceutical manufacturing not only leads to consequences to the local environment (7,8), but also in the case of antibiotics has potentially global consequences in terms of increasing risks for resistance development (9), limiting discharges is an urgent need to avoid a looming antibiotic resistance crisis (10).

The paper was also highlighted by the Centre for Antibiotic Resistance Research, and can be read here or here.

References

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Gunnarsson L, Larsson DGJ: Can branding and price of pharmaceuticals guide informed choices towards improved pollution control during manufacturing? Journal of Cleaner Production, 171, 137–146 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.247

- Hsu A, Alexandre N, Cohen S, Jao P, Khusainova E: 2016 Environmental Performance Index. Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA (2016). http://epi.yale.edu/reports/2016-report

- Transparency International: Corruption Perceptions Index 2014. Transparency International, Berlin, Germany (2014). http://www.transparency.org/cpi2014/in_detail

- Larsson DGJ, Fick J: Transparency throughout the production chain–a way to reduce pollution from the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals? Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 53, 161–163 (2009). doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.01.008

- Ågerstrand M, Berg C, Björlenius B, Breitholtz M, Brunström B, Fick J, Gunnarsson L, Larsson DGJ, Sumpter JP, Tysklind M, Rudén C: Improving environmental risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals. Environmental Science & Technology, 49, 5336–5345 (2015). doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b00302

- Industry Roadmap for Progress on Combating Antimicrobial Resistance: Industry Roadmap for Progress on Combating Antimicrobial Resistance – September 2016. (2016). http://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Roadmap-for-Progress-on-AMR-FINAL.pdf

- Larsson DGJ, de Pedro C, Paxeus N: Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 148, 751–755 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.008

- aus der Beek T, Weber FA, Bergmann A, Hickmann S, Ebert I, Hein A, Küster A: Pharmaceuticals in the environment–Global occurrences and perspectives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35, 823–835 (2016). doi:10.1002/etc.3339

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environment International, 86, 140–149 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Time to limit antibiotic pollution. The Medicine Maker, 0416, 302, 17–18 (2016). [Paper link]

Published paper: Environmental factors leading to resistance

Myself, Joakim Larsson and Erik Kristiansson have written a review on the environmental factors that influence development and spread of antibiotic resistance, which was published today in FEMS Microbiology Reviews. The review (1) builds on thoughts developed in the latter parts of my PhD thesis (2), and seeks to provide a synthesis knowledge gained from different subfields towards the current understanding of evolutionary and ecological processes leading to clinical appearance of resistance genes, as well as the important environmental dispersal barriers preventing spread of resistant pathogens.

We postulate that emergence of novel resistance factors and mobilization of resistance genes are likely to occur continuously in the environment. However, the great majority of such genetic events are unlikely to lead to establishment of novel resistance factors in bacterial populations, unless there is a selection pressure for maintaining them or their fitness costs are negligible. To enable measures to prevent resistance development in the environment, it is therefore critical to investigate under what conditions and to what extent environmental selection for resistance takes place. Selection for resistance is likely less important for the dissemination of resistant bacteria, but will ultimately depend on how well the species or strain in question thrives in the external environment. Metacommunity theory (3,4) suggests that dispersal ability is central to this process, and therefore opportunistic pathogens with their main habitat in the environment may play an important role in the exchange of resistance factors between humans and the environment. Understanding the dispersal barriers hindering this exchange is not only key to evaluate risks, but also to prevent resistant pathogens, as well as novel resistance genes, from reaching humans.

Towards the end of the paper, we suggest certain environments that seem to be more important from a risk management perspective. We also discuss additional problems linked to the development of antibiotic resistance, such as increased evolvability of bacterial genomes (5) and which other types of genes that may be mobilized in the future, should the development continue (1,6). In this review, we also further develop thoughts on the relative risks of re-recruiting and spreading well-known resistance factors already circulating in pathogens, versus recruitment of completely novel resistance genes from environmental bacteria (7). While the latter case is likely to be very rare, and thus almost impossible to quantify the risks for, the consequences of such (potentially one-time) events can be dire.

I personally think that this is one of the best though-through pieces I have ever written, and since it is open access and (in my biased opinion) written in a fairly accessible way, I recommend everyone to read it. It builds on the ecological theories for resistance ecology developed by, among others, Fernando Baquero and José Martinez (8-13). Over the last year, it has been stressed several times at meetings (e.g. at the EDAR conferences in August) that there is a need to develop an ecological framework for antibiotic resistance genes. I think this paper could be one of the foundational pillars on such an endeavor and look forward to see how it will fit into the growing literature on the subject!

References

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, accepted manuscript (2017). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Bengtsson-Palme J: Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a contribution from metagenomic studies. Doctoral thesis (medicine), Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 2016. [Link]

- Bengtsson J: Applied (meta)community ecology: diversity and ecosystem services at the intersection of local and regional processes. In: Verhoef HA, Morin PJ (eds.). Community Ecology: Processes, Models, and Applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 115–130 (2009).

- Leibold M, Norberg J: Biodiversity in metacommunities: Plankton as complex adaptive systems? Limnology and Oceanography, 1278–1289 (2004).

- Gillings MR, Stokes HW: Are humans increasing bacterial evolvability? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 27, 346–352 (2012).

- Gillings MR: Evolutionary consequences of antibiotic use for the resistome, mobilome and microbial pangenome. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 4 (2013).

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 369 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1

- Baquero F, Alvarez-Ortega C, Martinez JL: Ecology and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 1, 469–476 (2009).

- Baquero F, Tedim AP, Coque TM: Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 15 (2013).

- Berendonk TU, Manaia CM, Merlin C et al.: Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 310–317 (2015).

- Hiltunen T, Virta M, Laine A-L: Antibiotic resistance in the wild: an eco-evolutionary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372 (2017) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0039.

- Martinez JL: Bottlenecks in the transferability of antibiotic resistance from natural ecosystems to human bacterial pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2, 265 (2011).

- Salyers AA, Amábile-Cuevas CF: Why are antibiotic resistance genes so resistant to elimination? Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 41, 2321–2325 (1997).

Published paper: 76 new metallo-beta-lactamases

Today, Microbiome put online a paper lead-authored by my colleague Fanny Berglund – one of Erik Kristiansson‘s brilliant PhD students – in which we identify 76 novel metallo-ß-lactamases (1). This feat was made possible because of a new computational method designed by Fanny, which uses a hidden Markov model based on known B1 metallo-ß-lactamases. We analyzed over 10,000 bacterial genomes and plasmids and over 5 terabases of metagenomic data and could thereby predict 76 novel genes. These genes clustered into 59 new families of metallo-β-lactamases (given a 70% identity threshold). We also verified the functionality of 21 of these genes experimentally, and found that 18 were able to hydrolyze imipenem when inserted into Escherichia coli. Two of the novel genes contained atypical zinc-binding motifs in their active sites. Finally, we show that the B1 metallo-β-lactamases can be divided into five major groups based on their phylogenetic origin. It seems that nearly all of the previously characterized mobile B1 β-lactamases we identify in this study were likely to have originated from chromosomal genes present in species within the Proteobacteria, particularly Shewanella spp.

This study more than doubles the number of known B1 metallo-β-lactamases. As with the study by Boulund et al. (2) which we published last month on computational discovery of novel fluoroquinolone resistance genes (which used a very similar approach but on a completely different type of genes), this study also supports the hypothesis that environmental bacterial communities act as sources of uncharacterized antibiotic resistance genes (3-7). Fanny have done a fantastic job on this paper, and I highly recommend reading it in its entirety (it’s open access so you have virtually no excuse not to). It can be found here.

References

- Berglund F, Marathe NP, Österlund T, Bengtsson-Palme J, Kotsakis S, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ, Kristiansson E: Identification of 76 novel B1 metallo-β-lactamases through large-scale screening of genomic and metagenomic data. Microbiome, 5, 134 (2017). doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0353-8

- Boulund F, Berglund F, Flach C-F, Bengtsson-Palme J, Marathe NP, Larsson DGJ, Kristiansson E: Computational discovery and functional validation of novel fluoroquinolone resistance genes in public metagenomic data sets. BMC Genomics, 18, 682 (2017). doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4064-0

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 369 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1

- Allen HK, Donato J, Wang HH et al.: Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 8, 251–259 (2010).

- Berendonk TU, Manaia CM, Merlin C et al.: Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 310–317 (2015).

- Martinez JL: Bottlenecks in the transferability of antibiotic resistance from natural ecosystems to human bacterial pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2, 265 (2011).

- Finley RL, Collignon P, Larsson DGJ et al.: The scourge of antibiotic resistance: the important role of the environment. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 57, 704–710 (2013).