Published paper: benchmarking resistance gene identification

Since F1000Research uses a somewhat different publication scheme than most journals, I still haven’t understood if this paper is formally published after peer review, but I start to assume it is. There have been very little changes since the last version, so hence I will be lazy and basically repost what I wrote in April when the first version (the “preprint”) was posted online. The paper (1) is the result of a workshop arranged by the JRC in Italy in 2017. It describes various challenges arising from the process of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines in the identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next generation sequencing data.

The paper discusses issues about the benchmarking datasets used, testing samples, evaluation criteria for the performance of different tools, and how the benchmarking dataset should be created and distributed. Specially, we address the following questions:

- How should a benchmark strategy handle the current and expanding universe of NGS platforms?

- What should be the quality profile (in terms of read length, error rate, etc.) of in silico reference materials?

- Should different sets of reference materials be produced for each platform? In that case, how to ensure no bias is introduced in the process?

- Should in silico reference material be composed of the output of real experiments, or simulated read sets? If a combination is used, what is the optimal ratio?

- How is it possible to ensure that the simulated output has been simulated “correctly”?

- For real experiment datasets, how to avoid the presence of sensitive information?

- Regarding the quality metrics in the benchmark datasets (e.g. error rate, read quality), should these values be fixed for all datasets, or fall within specific ranges? How wide can/should these ranges be?

- How should the benchmark manage the different mechanisms by which bacteria acquire resistance?

- What is the set of resistance genes/mechanisms that need to be included in the benchmark? How should this set be agreed upon?

- Should datasets representing different sample types (e.g. isolated clones, environmental samples) be included in the same benchmark?

- Is a correct representation of different bacterial species (host genomes) important?

- How can the “true” value of the samples, against which the pipelines will be evaluated, be guaranteed?

- What is needed to demonstrate that the original sample has been correctly characterised, in case real experiments are used?

- How should the target performance thresholds (e.g. specificity, sensitivity, accuracy) for the benchmark suite be set?

- What is the impact of these performance thresholds on the required size of the sample set?

- How can the benchmark stay relevant when new resistance mechanisms are regularly characterized?

- How is the continued quality of the benchmark dataset ensured?

- Who should generate the benchmark resource?

- How can the benchmark resource be efficiently shared?

Of course, we have not answered all these questions, but I think we have come down to a decent description of the problems, which we see as an important foundation for solving these issues and implementing the benchmarking standard. Some of these issues were tackled in our review paper from last year on using metagenomics to study resistance genes in microbial communities (2). The paper also somewhat connects to the database curation paper we published in 2016 (3), although this time the strategies deal with the testing datasets rather than the actual databases. The paper is the first outcome of the workshop arranged by the JRC on “Next-generation sequencing technologies and antimicrobial resistance” held October 4-5 2017 in Ispra, Italy. You can find the paper here (it’s open access).

On another note, the new paper describing the UNITE database (4) has now got a formal issue assigned to it, as has the paper on tandem repeat barcoding in fungi published in Molecular Ecology Resources last year (5).

References and notes

- Angers-Loustau A, Petrillo M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Berendonk T, Blais B, Chan KG, Coque TM, Hammer P, Heß S, Kagkli DM, Krumbiegel C, Lanza VF, Madec J-Y, Naas T, O’Grady J, Paracchini V, Rossen JWA, Ruppé E, Vamathevan J, Venturi V, Van den Eede G: The challenges of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines in the identification of antimicrobial resistance determinants using next generation sequencing technologies. F1000Research, 7, 459 (2018). doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14509.1

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ, Kristiansson E: Using metagenomics to investigate human and environmental resistomes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 72, 2690–2703 (2017). doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx199

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Boulund F, Edström R, Feizi A, Johnning A, Jonsson VA, Karlsson FH, Pal C, Pereira MB, Rehammar A, Sánchez J, Sanli K, Thorell K: Strategies to improve usability and preserve accuracy in biological sequence databases. Proteomics, 16, 18, 2454–2460 (2016). doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600034

- Nilsson RH, Larsson K-H, Taylor AFS, Bengtsson-Palme J, Jeppesen TS, Schigel D, Kennedy P, Picard K, Glöckner FO, Tedersoo L, Saar I, Kõljalg U, Abarenkov K: The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Research, 47, D1, D259–D264 (2019). doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1022

- Wurzbacher C, Larsson E, Bengtsson-Palme J, Van den Wyngaert S, Svantesson S, Kristiansson E, Kagami M, Nilsson RH: Introducing ribosomal tandem repeat barcoding for fungi. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19, 1, 118–127 (2019). doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12944

Published paper: Diarrhea-causing bacteria in the Choqueyapu River in Bolivia

My first original paper of the year was just published in PLoS ONE. This is a collaboration with Åsa Sjöling’s group at the Karolinska Institute and the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in Bolivia, and the project has been largely run by Jessica Guzman-Otazo.

Poor drinking water quality is a major cause of diarrhea, especially in the absence of well-working sewage treatment systems. In the study, we investigate the numbers of bacteria causing diarrhea (or actually, marker genes for those bacteria) in water, soil and vegetable samples from the Choqueyapu River area in La Paz – Bolivia’s third largest city (1). The river receives sewage and wastewater from industries and hospitals while flowing through La Paz. We found that levels of ETEC – a bacterium that causes severe diarrhea – were much higher in the city than upstream of it, including at a site where the river water is used for irrigation of crops.

In addition, several multi-resistant bacteria could be isolated from the samples, of which many were emerging, globally spreading, multi-resistant variants. The results of the study indicate that there is a real risk for spreading of diarrheal diseases by using the contaminated water for drinking and irrigation (2,3). Furthermore, the identification of multi-resistant bacteria that can cause human diseases show that water contamination is an important route through which antibiotic resistance can be transferred from the environment back to humans (4).

The study was published in PLoS ONE and can be found here.

References

- Guzman-Otazo J, Gonzales-Siles L, Poma V, Bengtsson-Palme J, Thorell K, Flach C-F, Iñiguez V, Sjöling Å: Diarrheal bacterial pathogens and multi-resistant enterobacteria in the Choqueyapu River in La Paz, Bolivia. PLoS ONE, 14, 1, e0210735 (2019). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210735

- Graham DW, Collignon P, Davies J, Larsson DGJ, Snape J: Underappreciated Role of Regionally Poor Water Quality on Globally Increasing Antibiotic Resistance. Environ Sci Technol 141001154428000 (2014). doi: 10.1021/es504206x

- Bengtsson-Palme J: Antibiotic resistance in the food supply chain: Where can sequencing and metagenomics aid risk assessment? Current Opinion in Food Science, 14, 66–71 (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2017.01.010

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

Published book chapter: Resistance Risks in the Environment

Time flies, and my first 2019 publication (wait what?) is now out! It’s a chapter in the book “Management of Emerging Public Health Issues and Risks: Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Changing Environment” (1), edited by Benoit Roig, Karine Weiss and Véronique Thireau. I have to confess to not having read the other chapters in the book yet, but I think the subject is exciting and hope for a lot of good reading over Christmas here!

My chapter deals with assessment and management of risks associated with antibiotic resistance in the environment (2), and particularly I make an attempt at clarifying the different types of risks and how to deal with them. In short, I partition resistance risks into two categories: dissemination risks and risks for acquisition of new types of resistance (see also 3). While the former category largely encompasses quantifiable risks, the latter is to a large extent impossible (or at least extremely hard) to quantify with current means. This means that we need to be a bit more creative in assessing, prioritizing and managing these risks. Some lessons can be learnt from other fields dealing with very uncertain (and rare) risks, such as asteroid impact assessment, nuclear energy accidents and ecosystem destabilization (4,5). Incorporating elements from such risk management schemes will be necessary to understand and delay emergence of novel resistance in the future.

All these aspects are further discussed in the book chapter (2), which I encourage everyone working with environmental antibiotic resistance risks to read!

References

- Roig B, Weiss K, Thoreau V (Eds.) Management of Emerging Public Health Issues and Risks: Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Changing Environment. Academic Press/Elsevier, UK (2019). doi: 10.1016/C2016-0-00995-6

- Bengtsson-Palme J: Assessment and management of risks associated with antibiotic resistance in the environment. In: Roig B, Weiss K, Thoreau V (Eds.) Management of Emerging Public Health Issues and Risks: Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Changing Environment, 243–263. Elsevier, UK (2019). doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813290-6.00010-X

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- WBGU GACOGC: World in Transition: Strategies for Managing Global Environmental Risks. Springer

Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg (2000). - Government Office for Science: Blackett Review of High Impact Low Probability Events. Department for

Business, Innovation and Skills, London (2011).

Published paper: The global topsoil microbiome

I’m really late at this ball for a number of reasons, but last week Nature published our paper on the structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome (1). This paper has a long story, but in short I got contacted by Mohammad Bahram (the first author) about two years ago about a project using metagenomic sequencing to look at a lot of soil samples for patterns of antibiotic resistance gene abundances and diversity. The project had made the interesting discovery that resistance gene abundances were linked to the ratio of fungi and bacteria (so that more fungi was linked to more resistance genes). During the following year, we together worked on deciphering these discoveries, which are now published in Nature. The paper also deals with the taxonomic patterns linked to geography (1), but as evident from the above, my main contribution here has been on the antibiotic resistance side.

In short, we find that:

- Bacterial diversity is highest in temperate habitats, and lower both closer to the equator and the poles

- For bacteria, the diversity of biological functions follows the same pattern, but for fungi, the functional diversity is higher closer to the poles and the equator

- Higher abundance of fungi is linked to higher abundance and diversity of antibiotic resistance genes. Specifically, this is related to known antibiotic producing fungal lineages, such as Penicillium and Oidiodendron. There also seems to be a link between the Actinobacteria, encompassing the antibiotic-producing bacterial genus of Streptomyces and higher resistance gene diversity.

- Similar relationships between the fungus-like Oomycetes and resistance genes was also found in ocean samples from the Tara Oceans project (2)

The results of this study indicate that both environmental filtering and niche differentiation determine soil microbial composition, and that the role of dispersal limitation is minor at this scale. Soil pH and precipitation seems to be the strongest drivers of community composition. Furthermore, we interpret our data to reveal that inter-kingdom antagonism is important in structuring microbial communities. This speaks against the notion put forward that antibiotic resistance genes might not have a resistance function in natural settings (3). That said, the most likely explanation here is probably a bit of both warfare and repurposing of genes. Soil seems to be the largest untapped source of resistance genes for human pathogens (4), and the finding that natural antagonism may be driving resistance gene diversification and enrichment may be important for future management of environmental antibiotic resistance (5,6).

It was really great to work with Mohammad and his team, and I sure hope that we will collaborate again in the future. The entire paper can be found in the issue of Nature coming out this week, and is already online at Nature’s website.

References

- Bahram M°, Hildebrand F°, Forslund SK, Anderson JL, Soudzilovskaia NA, Bodegom PM, Bengtsson-Palme J, Anslan S, Coelho LP, Harend H, Huerta-Cepas J, Medema MH, Maltz MR, Mundra S, Olsson PA, Pent M, Põlme S, Sunagawa S, Ryberg M, Tedersoo L, Bork P: Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature, 560, 233–237 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6

- Sunagawa S et al. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348, 6237, 1261359 (2015). doi: 10.1126/science.1261359

- Aminov RI: The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Environmental Microbiology, 11, 12, 2970-2988 (2009). doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01972.x

- Bengtsson-Palme J: The diversity of uncharacterized antibiotic resistance genes can be predicted from known gene variants – but not always. Microbiome, 6, 125 (2018). doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0508-2

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, 117, 132–138 (2018).

Blog post at Nature Microbiology Community

I have just published a popular-science-for-scientists type of post at the Nature Microbiology Community about my recent paper published in Microbiome. I personally think that it might be worth a read, so feel free to head over here and read it!

Published paper: Predicting the uncharacterized resistome

Over the weekend, Microbiome put online my most recent paper (1) – a project which started as an idea I got when I finished up my PhD thesis in 2016. One of my main points in the thesis (2), which was also made again on our recent review on environmental factors influencing resistance development (3), is that the greatest risks associated with antibiotic resistance in the environment may not be the resistance genes already circulating in pathogens (which are relatively easily quantified), but the ones associated with recruitment of novel resistance genes from bacteria in the environment (2-4). The latter genes are, however, impossible to quantify due to the fact that they are unknown. But what if we could use knowledge of the diversity and abundance of known resistance genes to estimate the same properties of the yet uncharacterized resistome? That would be a great advantage in e.g. ranking of risk environments, as then some property that is easily monitored can be used to inform risk management of both known and unknown resistance factors.

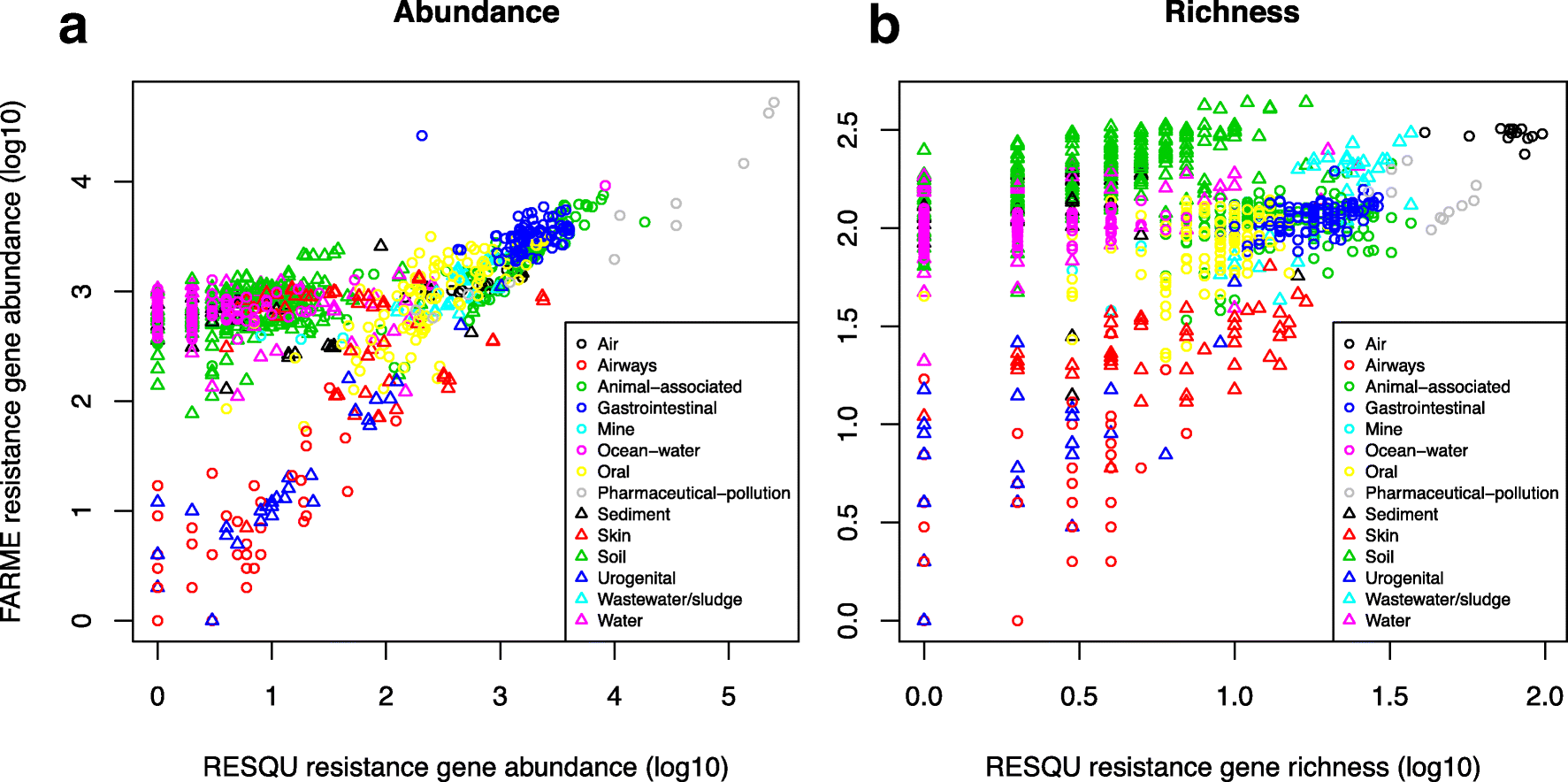

This just published paper explores this possibility, by quantifying the abundance and diversity of resistance genes in 1109 metagenomes from various environments (1). I have taken two different approaches. First, I took out smaller subsets of genes from the reference database (in this case Resqu, a database of antibiotic resistance genes with verified resistance functions, detected on mobile genetic elements), and used those subsets to estimate resistome diversity and abundance in the 1109 metagenomes. Then these predictions were compared to the results of the entire database. I then, in a second step, investigated if these predictions could be extended to a set of truly novel resistance genes, i.e. the resistance genes present in the FARME database, collecting data from functional metagenomics inserts (5,6).

The results show that generally the diversity and abundance of known antibiotic resistance genes can be used to predict the same properties of undescribed resistance genes (see figure above). However, the extent of this predictability is, importantly, dependent on the type of environment investigated. The study also shows that carefully selected small sets of resistance genes can describe total resistance gene diversity remarkably well. This means that knowledge gained from large-scale quantifications of known resistance genes can be utilized as a proxy for unknown resistance factors. This is important for current and proposed monitoring efforts for environmental antibiotic resistance (7-11) and has implications for the design of risk ranking strategies and the choices of measures and methods for describing resistance gene abundance and diversity in the environment.

The study also investigated which diversity measures were best suited to estimate total diversity. Surprisingly, some diversity measures described the total diversity of resistance genes remarkably bad. Most prominently, the Simpson diversity index consistently showed poor performance, and while the Shannon index performed relatively better, there is still no reason to select the Shannon index over normalized (rarefied) richness of resistance genes. The ACE estimator fluctuated substantially compared to the other diversity measures, while the Chao1 estimator more consistently showed performance very similar to richness. Therefore, either richness or the Chao1 estimator should be used for ranking resistance gene diversity, while the Shannon, Simpson, and ACE measures should be avoided.

Importantly, this study implies that the recruitment of novel antibiotic resistance genes from the environment to human pathogens is essentially random. Therefore, when ranking risks associated with antibiotic resistance in environmental settings, the knowledge gained from large-scale quantification of known resistance genes can be utilized as a proxy for the unknown resistance factors (although this proxy is not perfect). Thus, high-risk environments for resistance development and dissemination would, for example, be aquaculture, animal husbandry, discharges from antibiotic manufacturing, and untreated sewage (3,8,12-15). Further attention should probably be paid to antibiotic contaminated soils, as this study points to soils as a vast source of resistance genes not yet encountered in human pathogens. This has also been suggested previously by others (16-19). The results of this study can be used to guide monitoring efforts for environmental antibiotic resistance, to design risk ranking strategies, and to choose appropriate measures and methods for describing resistance gene abundance and diversity in the environment. The entire open access paper is available here.

References

- Bengtsson-Palme J: The diversity of uncharacterized antibiotic resistance genes can be predicted from known gene variants – but not always. Microbiome, 6, 125 (2018). doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0508-2

- Bengtsson-Palme J: Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a contribution from metagenomic studies. Doctoral thesis (medicine), Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 2016. [Link]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 369 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1

- Wallace JC, Port JA, Smith MN, Faustian EM: FARME DB: a functional antibiotic resistance element database. Database, 2017, baw165 (2017).

- Handelsman J, Rondon MR, Brady SF, Clardy J, Goodman RM: Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chemical Biology, 5, R245–249 (1998).

- Berendonk TU, Manaia CM, Merlin C, Fatta-Kassinos D, Cytryn E, Walsh F, et al.: Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 310–317 (2015).

- Pruden A, Larsson DGJ, Amézquita A, Collignon P, Brandt KK, Graham DW, et al.: Management options for reducing the release of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes to the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 878–885 (2013).

- Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Antimicrobials in agriculture and the environment: reducing unnecessary use and waste. O’Neill J, ed. London: Wellcome Trust & HM Government (2015).

- Angers-Loustau A, Petrillo M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Berendonk T, Blais B, Chan KG, Coque TM, Hammer P, Heß S, Kagkli DM, Krumbiegel C, Lanza VF, Madec J-Y, Naas T, O’Grady J, Paracchini V, Rossen JWA, Ruppé E, Vamathevan J, Venturi V, Van den Eede G: The challenges of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines in the identification of antimicrobial resistance determinants using next generation sequencing technologies. F1000Research, 7, 459 (2018). doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14509.1

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, 117, 132–138 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.041

- Allen HK, Donato J, Wang HH, Cloud-Hansen KA, Davies J, Handelsman J: Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 8, 251–259 (2010).

- Graham DW, Collignon P, Davies J, Larsson DGJ, Snape J: Underappreciated role of regionally poor water quality on globally increasing antibiotic resistance. Environmental Science & Technology, 48,11746–11747 (2014).

- Larsson DGJ: Pollution from drug manufacturing: review and perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B Biological Sciences, 369, 20130571 (2014).

- Cabello FC, Godfrey HP, Buschmann AH, Dölz HJ: Aquaculture as yet another environmental gateway to the development and globalisation of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16, e127–133 (2016).

- Forsberg KJ, Reyes A, Wang B, Selleck EM, Sommer MOA, Dantas G: The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science, 337, 1107–1111 (2012).

- Allen HK, Moe LA, Rodbumrer J, Gaarder A, Handelsman J: Functional metagenomics reveals diverse beta-lactamases in a remote Alaskan soil. ISME Journal, 3, 243–251 (2009).

- Riesenfeld CS, Goodman RM, Handelsman J: Uncultured soil bacteria are a reservoir of new antibiotic resistance genes. Environmental Microbiology, 6, 981–989 (2004).

- McGarvey KM, Queitsch K, Fields S: Wide variation in antibiotic resistance proteins identified by functional metagenomic screening of a soil DNA library. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78, 1708–1714 (2012).

Published paper: A Metaxa2 database for the arthropod COI locus

A few days ago I posted about that Bioinformatics had published our paper on the Metaxa2 Database Builder (1). Today, I am happy to report that PeerJ has published the first paper in which the database builder is used to create a new Metaxa2 (2) database! My colleagues at Ohio State University has used the software to build a database for the COI gene (3), which is commonly used in arthropod barcoding. The used region was extracted from COI sequences from arthropod whole mitochondrion genomes, and employed to create a database containing sequences from all major arthropod clades, including all insect orders, all arthropod classes and the Onychophora, Tardigrada and Mollusca outgroups.

Similar to what we did in our evaluation of taxonomic classifiers used on non-rRNA barcoding regions (4), we performed a cross-validation analysis to characterize the relationship between the Metaxa2 reliability score, an estimate of classification confidence, and classification error probability. We used this analysis to select a reliability score threshold which minimized error. We then estimated classification sensitivity, false discovery rate and overclassification, the propensity to classify sequences from taxa not represented in the reference database.

Since the database builder was still in its early inception stages when we started doing this work, the software itself saw several improvements because of this project. We believe that our work on the COI database, as well as on the recently released database builder software, will help researchers in designing and evaluating classification databases for metabarcoding on arthropods and beyond. The database is included in the new Metaxa2 2.2 release, and is also downloadable from the Metaxa2 Database Repository (1). The open access paper can be found here.

References

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Richardson RT, Meola M, Wurzbacher C, Tremblay ED, Thorell K, Kanger K, Eriksson KM, Bilodeau GJ, Johnson RM, Hartmann M, Nilsson RH: Metaxa2 Database Builder: Enabling taxonomic identification from metagenomic and metabarcoding data using any genetic marker. Bioinformatics, advance article (2018). doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty482

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Hartmann M, Eriksson KM, Pal C, Thorell K, Larsson DGJ, Nilsson RH: Metaxa2: Improved identification and taxonomic classification of small and large subunit rRNA in metagenomic data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15, 6, 1403–1414 (2015). doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12399

- Richardson RT, Bengtsson-Palme J, Gardiner MM, Johnson RM: A reference cytochrome c oxidase subunit I database curated for hierarchical classification of arthropod metabarcoding data. PeerJ, 6, e5126 (2018). doi: 10.7717/peerj.5126

- Richardson RT, Bengtsson-Palme J, Johnson RM: Evaluating and Optimizing the Performance of Software Commonly Used for the Taxonomic Classification of DNA Sequence Data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 17, 4, 760–769 (2017). doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12628

Published paper: Knowledge gaps for environmental antibiotic resistance

The outcomes from a workshop arranged by JPIAMR, the Swedish Research Council (VR) and CARe were just published as a short review paper in Environment International. In the paper, which was mostly moved forward by Prof. Joakim Larsson at CARe, we describe four major areas of knowledge gaps in the realm of environmental antibiotic resistance (1). We then highlight several important sub-questions within these areas. The broad areas we define are:

- What are the relative contributions of different sources of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria into the environment?

- What is the role of the environment as affected by anthropogenic inputs (e.g. pollution and other activities) on the evolution (mobilization, selection, transfer, persistence etc.) of antibiotic resistance?

- How significant is the exposure of humans to antibiotic resistant bacteria via different environmental routes, and what is the impact on human health?

- What technological, social, economic and behavioral interventions are effective to mitigate the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance via the environment?

Although much has been written on the topic before (e.g. 2-12), I think it is unique that we collect and explicitly point out areas in which we are lacking important knowledge to build accurate risk models and devise appropriate intervention strategies. The workshop was held in Gothenburg on the 27–28th of September 2017. The workshop leaders Joakim Larsson, Ana-Maria de Roda Husman and Ramanan Laxminarayan were each responsible for moderating a breakout group, and every breakout group was tasked to deal with knowledge gaps related to either evolution, transmission or interventions. The reports of the breakout groups were then discussed among all participants to clarify and structure the areas where more research is needed, which boiled down to the four overarching critical knowledge gaps described in the paper (1).

This is a short paper, and I think everyone with an interest in environmental antibiotic resistance should read it and reflect over its content (because, we may of course have overlooked some important aspect). You can find the paper here.

References

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, 117, 132–138 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.041

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Martinez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F: What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2015, 13:116–123. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3399

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 369 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1

- Ashbolt NJ, Amézquita A, Backhaus T, Borriello P, Brandt KK, Collignon P, et al.: Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) for Environmental Development and Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 993–1001 (2013)

- Pruden A, Larsson DGJ, Amézquita A, Collignon P, Brandt KK, Graham DW, et al.: Management options for reducing the release of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes to the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 878–85 (2013).

- Gillings MR: Evolutionary consequences of antibiotic use for the resistome, mobilome and microbial pangenome. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 4 (2013).

- Baquero F, Alvarez-Ortega C, Martinez JL: Ecology and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 1, 469–476 (2009).

- Baquero F, Tedim AP, Coque TM: Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 15 (2013).

- Berendonk TU, Manaia CM, Merlin C et al.: Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13, 310–317 (2015).

- Hiltunen T, Virta M, Laine A-L: Antibiotic resistance in the wild: an eco-evolutionary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372 (2017) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0039.

- Martinez JL: Bottlenecks in the transferability of antibiotic resistance from natural ecosystems to human bacterial pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2, 265 (2011).

Published paper: Selective concentrations for ciprofloxacin

My colleagues in Gothenburg have published a new paper in Environment International, in which I was involved in the bioinformatics analyses. In the paper, for which Nadine Kraupner did the lion’s share of the work, we establish minimal selective concentrations (MSCs) for resistance to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin in Escherichia coli grown in complex microbial communities (1). We also determine the community responses at the taxonomic and resistance gene levels. Nadine has made use of Sara Lundström’s aquarium system (2) to grow biofilms in the exposure of sublethal levels of antibiotics. Using the system, we find that 1 μg/L ciprofloxacin selects for the resistance gene qnrD, while 10 μg/L ciprofloxacin is required to detect changes of phenotypic resistance. In short, the different endpoints studied (and their corresponding MSCs) were:

- CFU counts from test tubes, grown on R2A plates with 2 mg/L ciprofloxain – MSC = 5 μg/L

- CFU counts from aquaria, grown on R2A plates with 0.25 or 2 mg/L ciprofloxain – MSC = 10 μg/L

- Chromosomal resistance mutations – MSC ~ 10 μg/L

- Increased resistance gene abundances, metagenomics – MSC range: 1 μg/L

- Changes to taxonomic diversity – 1 µg/L

- Changes to taxonomic community composition – MSC ~ 1-10 μg/L

We have previously reported a predicted no-effect concentration for resistance of 0.064 µg/L for ciprofloxacin (3), which corresponds fairly well with the MSCs determined experimentally here, being around a factor of ten off. However, we cannot exclude that in other experimental systems, the selective effects of ciprofloxacin could be even lower and thus the predicted PNEC may still be relevant. The selective concentrations we report for ciprofloxacin are close to those that have been reported in sewage treatment plants (3-5), suggesting the possibility for weak selection of resistance. Several recent reports have underscored the need to populate the this far conceptual models for resistance development in the environment with actual numbers (6-10). Determining selective concentrations for different antibiotics in actual community settings is an important step on the road towards building accurate quantitative models for resistance emergence and propagation.

References

- Kraupner N, Ebmeyer S, Bengtsson-Palme J, Fick J, Kristiansson E, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ: Selective concentration for ciprofloxacin in Escherichia coli grown in complex aquatic bacterial biofilms. Environment International, 116, 255–268 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.029 [Paper link]

- Lundström SV, Östman M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Rutgersson C, Thoudal M, Sircar T, Blanck H, Eriksson KM, Tysklind M, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ: Minimal selective concentrations of tetracycline in complex aquatic bacterial biofilms. Science of the Total Environment, 553, 587–595 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.103 [Paper link]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ: Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environment International, 86, 140-149 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015

- Michael I, Rizzo L, McArdell CS, Manaia CM, Merlin C, Schwartz T, Dagot C, Fatta-Kassinos D: Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: a review. Water Research, 47, 957–995 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.027

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Hammarén R, Pal C, Östman M, Björlenius B, Flach C-F, Kristiansson E, Fick J, Tysklind M, Larsson DGJ: Elucidating selection processes for antibiotic resistance in sewage treatment plants using metagenomics. Science of the Total Environment, 572, 697–712 (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.228

- Ågerstrand M, Berg C, Björlenius B, Breitholtz M, Brunstrom B, Fick J, Gunnarsson L, Larsson DGJ, Sumpter JP, Tysklind M, Rudén C: Improving environmental risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals. Environmental Science and Technology (2015). doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b00302

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ: Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42, 1, 68–80 (2018). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

- Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance: JPIAMR Workshop on Environmental Dimensions of AMR: Summary and recommendations. JPIAMR (2017). [Link]

- Angers A, Petrillo P, Patak, A, Querci M, Van den Eede G: The Role and Implementation of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies in the Coordinated Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance. JRC Conference and Workshop Report, EUR 28619 (2017). doi: 10.2760/745099

- Larsson DGJ, Andremont A, Bengtsson-Palme J, Brandt KK, de Roda Husman AM, Fagerstedt P, Fick J, Flach C-F, Gaze WH, Kuroda M, Kvint K, Laxminarayan R, Manaia CM, Nielsen KM, Ploy M-C, Segovia C, Simonet P, Smalla K, Snape J, Topp E, van Hengel A, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Virta MPJ, Wellington EM, Wernersson A-S: Critical knowledge gaps and research needs related to the environmental dimensions of antibiotic resistance. Environment International, in press (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.041

New preprint: benchmarking resistance gene identification

This weekend, F1000Research put online the non-peer-reviewed version of the paper resulting from a workshop arranged by the JRC in Italy last year (1). (I will refer to this as a preprint, but at F1000Research the line is quite blurry between preprint and published paper.) The paper describes various challenges arising from the process of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines (2) in the identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next generation sequencing data.

The paper discusses issues about the benchmarking datasets used, testing samples, evaluation criteria for the performance of different tools, and how the benchmarking dataset should be created and distributed. Specially, we address the following questions:

- How should a benchmark strategy handle the current and expanding universe of NGS platforms?

- What should be the quality profile (in terms of read length, error rate, etc.) of in silico reference materials?

- Should different sets of reference materials be produced for each platform? In that case, how to ensure no bias is introduced in the process?

- Should in silico reference material be composed of the output of real experiments, or simulated read sets? If a combination is used, what is the optimal ratio?

- How is it possible to ensure that the simulated output has been simulated “correctly”?

- For real experiment datasets, how to avoid the presence of sensitive information?

- Regarding the quality metrics in the benchmark datasets (e.g. error rate, read quality), should these values be fixed for all datasets, or fall within specific ranges? How wide can/should these ranges be?

- How should the benchmark manage the different mechanisms by which bacteria acquire resistance?

- What is the set of resistance genes/mechanisms that need to be included in the benchmark? How should this set be agreed upon?

- Should datasets representing different sample types (e.g. isolated clones, environmental samples) be included in the same benchmark?

- Is a correct representation of different bacterial species (host genomes) important?

- How can the “true” value of the samples, against which the pipelines will be evaluated, be guaranteed?

- What is needed to demonstrate that the original sample has been correctly characterised, in case real experiments are used?

- How should the target performance thresholds (e.g. specificity, sensitivity, accuracy) for the benchmark suite be set?

- What is the impact of these performance thresholds on the required size of the sample set?

- How can the benchmark stay relevant when new resistance mechanisms are regularly characterized?

- How is the continued quality of the benchmark dataset ensured?

- Who should generate the benchmark resource?

- How can the benchmark resource be efficiently shared?

Of course, we have not answered all these questions, but I think we have come down to a decent description of the problems, which we see as an important foundation for solving these issues and implementing the benchmarking standard. Some of these issues were tackled in our review paper from last year on using metagenomics to study resistance genes in microbial communities (3). The paper also somewhat connects to the database curation paper we published in 2016 (4), although this time the strategies deal with the testing datasets rather than the actual databases. The paper is the first outcome of the workshop arranged by the JRC on “Next-generation sequencing technologies and antimicrobial resistance” held October 4-5 last year in Ispra, Italy. You can find the paper here (it’s open access).

References and notes

- Angers-Loustau A, Petrillo M, Bengtsson-Palme J, Berendonk T, Blais B, Chan KG, Coque TM, Hammer P, Heß S, Kagkli DM, Krumbiegel C, Lanza VF, Madec J-Y, Naas T, O’Grady J, Paracchini V, Rossen JWA, Ruppé E, Vamathevan J, Venturi V, Van den Eede G: The challenges of designing a benchmark strategy for bioinformatics pipelines in the identification of antimicrobial resistance determinants using next generation sequencing technologies. F1000Research, 7, 459 (2018). doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14509.1

- You may remember that I hate the term “pipeline” for bioinformatics protocols. I would have preferred if it was called workflows or similar, but the term “pipeline” has taken hold and I guess this is a battle where I have essentially lost. The bioinformatics workflows will be known as pipelines, for better and worse.

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ, Kristiansson E: Using metagenomics to investigate human and environmental resistomes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 72, 2690–2703 (2017). doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx199

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Boulund F, Edström R, Feizi A, Johnning A, Jonsson VA, Karlsson FH, Pal C, Pereira MB, Rehammar A, Sánchez J, Sanli K, Thorell K: Strategies to improve usability and preserve accuracy in biological sequence databases. Proteomics, 16, 18, 2454–2460 (2016). doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600034